Friday, August 30, 2013

Why Indian Students Still Fear Taking Competitive ...

Why Indian Students Still Fear Taking Competitive ...: As summer temperatures soar, the tensions of students rise proportionally. With competitive exams at the center for most of the aspirant...

Supermassive Black Hole Sagittarius A*

The center of the Milky Way galaxy, with the supermassive black hole

Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), located in the middle, is revealed in these

images. As described in our press release, astronomers have used NASA’s

Chandra X-ray Observatory to take a major step in understanding why

material around Sgr A* is extraordinarily faint in X-rays.

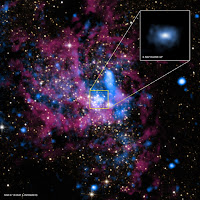

The large image contains X-rays from Chandra in blue and infrared emission from the Hubble Space Telescope in red and yellow. The inset shows a close-up view of Sgr A* in X-rays only, covering a region half a light year wide. The diffuse X-ray emission is from hot gas captured by the black hole and being pulled inwards. This hot gas originates from winds produced by a disk-shaped distribution of young massive stars observed in infrared observations.

These new findings are the result of one of the biggest observing campaigns ever performed by Chandra. During 2012, Chandra collected about five weeks worth of observations to capture unprecedented X-ray images and energy signatures of multi-million degree gas swirling around Sgr A*, a black hole with about 4 million times the mass of the Sun. At just 26,000 light years from Earth, Sgr A* is one of very few black holes in the universe where we can actually witness the flow of matter nearby.

The authors infer that less than 1% of the material initially within the black hole’s gravitational influence reaches the event horizon, or point of no return, because much of it is ejected. Consequently, the X-ray emission from material near Sgr A* is remarkably faint, like that of most of the giant black holes in galaxies in the nearby Universe.

The captured material needs to lose heat and angular momentum before being able to plunge into the black hole. The ejection of matter allows this loss to occur.

This work should impact efforts using radio telescopes to observe and understand the “shadow” cast by the event horizon of Sgr A* against the background of surrounding, glowing matter. It will also be useful for understanding the impact that orbiting stars and gas clouds might make with the matter flowing towards and away from the black hole.

The large image contains X-rays from Chandra in blue and infrared emission from the Hubble Space Telescope in red and yellow. The inset shows a close-up view of Sgr A* in X-rays only, covering a region half a light year wide. The diffuse X-ray emission is from hot gas captured by the black hole and being pulled inwards. This hot gas originates from winds produced by a disk-shaped distribution of young massive stars observed in infrared observations.

These new findings are the result of one of the biggest observing campaigns ever performed by Chandra. During 2012, Chandra collected about five weeks worth of observations to capture unprecedented X-ray images and energy signatures of multi-million degree gas swirling around Sgr A*, a black hole with about 4 million times the mass of the Sun. At just 26,000 light years from Earth, Sgr A* is one of very few black holes in the universe where we can actually witness the flow of matter nearby.

The authors infer that less than 1% of the material initially within the black hole’s gravitational influence reaches the event horizon, or point of no return, because much of it is ejected. Consequently, the X-ray emission from material near Sgr A* is remarkably faint, like that of most of the giant black holes in galaxies in the nearby Universe.

The captured material needs to lose heat and angular momentum before being able to plunge into the black hole. The ejection of matter allows this loss to occur.

This work should impact efforts using radio telescopes to observe and understand the “shadow” cast by the event horizon of Sgr A* against the background of surrounding, glowing matter. It will also be useful for understanding the impact that orbiting stars and gas clouds might make with the matter flowing towards and away from the black hole.

The paper is available online and is published in the journal Science.

The first author is Q.Daniel Wang from University of Massachusetts at

Amherst, MA; and the co-authors are Michael Nowak from Massachusetts

Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, MA; Sera Markoff from

University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands, Fred Baganoff from MIT;

Sergei Nayakshin from University of Leicester in the UK; Feng Yuan from

Shanghai Astronomical Observatory in China; Jorge Cuadra from

Pontificia Universidad de Catolica de Chile in Chile; John Davis from

MIT; Jason Dexter from University of California, Berkeley, CA; Andrew

Fabian from University of Cambridge in the UK; Nicolas Grosso from

Universite de Strasbourg in France; Daryl Haggard from Northwestern

University in Evanston, IL; John Houck from MIT; Li Ji from Purple

Mountain Observatory in Nanjing, China; Zhiyuan Li from Nanjing

University in China; Joseph Neilsen from Boston University in Boston,

MA; Delphine Porquet from Universite de Strasbourg in France; Frank

Ripple from University of Massachusetts at Amherst, MA and

Roman Shcherbakov from University of Maryland, in College Park, MD.

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/UMass/D.Wang et al., IR: NASA/STScI

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)